Us Brits love a queue but not so much when it comes to window shopping online. Since the pandemic struck, we’ve seen a rise in online queuing systems, especially in certain retail categories. This is our view on why customer experience thinking should be embedded across CX and technical teams alike.

Before you get into this article, I’d like to make a caveat about this piece. The health and protection of employees in all companies is the most important thing right now. The reason for the rise in the use of queue systems is, primarily, to help companies adhere to social distancing at their physical stores, and their rapid implementation by teams should be applauded. This article is simply to look at how we can learn from some of the CX challenges many retailers are currently facing online, and how we can restructure digital platforms and services to enhance our CX and the opportunities this could offer.

Since the outbreak of the pandemic, queuing has become a large part of our lives. For us in the UK, it may even be the thing we’ve been most comfortable with since our lives have been turned upside down with social distancing measures. However, queuing for our online products, through the integration of systems such as Queue-it, has felt particularly alien. As customers, we’ve become accustomed to the Amazon-Prime-way-of-life. Products consistently available on demand, at the touch of our fingers. It says something that for many, as suppliers ran out of delivery slots, a weekly trip to the supermarket was something of a throwback to a bygone era rather than the continuation of business as usual. Therefore, when the ability to shop on demand is taken away from you as a consumer, you can’t help but feel dissatisfied and frustrated. And, subconsciously, it may cause customers to form a negative feeling towards the retailer with whom they’re trying to spend money.

I think it’s important to look at why these systems have been introduced, and how we can improve this experience. With a long recession predicted as we come out into a post COVID-19 world, convincing customers they should part with their precious cash and spend it with you, will become increasingly important.

The Queue-It UI became a common sight during lockdown, but what alternatives are there to this type of queuing system?

The process of buying online will differ from business to business and, although the broad stroke of ‘eCommerce’ to describe such a wide array of businesses is always dangerous, it’s still interesting to look at the similarities of eCommerce customers.

Although some customers will convert within a single session, a large portion of eCommerce revenue is like to come from customer journeys which involve multiple sessions. Wolfgang Digital’s 2020 KPI study revealed that, on average, customers would only convert after close to five sessions on your site. This makes sense, as customers’ habits have changed. They are likely to want to shop around from the comfort of their living rooms or on their commutes. The speed at which you can perform prices or compare products is a unique aspect of eCommerce and one of the reasons why customers have flocked to it in their droves. Digging into the data within Wolfgang Digital’s study shows that, the more time a customer visits an eCommerce platform, the more likely they are to add items to their basket, and ultimately buy products. As such, businesses that aim to reduce the friction between these sessions and ensure that they can capture that sale as soon as the customer’s mind has been made up, are likely at a key competitive advantage.

These kinds of customers are essentially window shopping. They may be browsing either because they’re bored and with their device or are actively shopping around for a particular item. They might not be purchasing something immediately, but they may come back to your site to complete a purchase once they’ve finished their shopping around. It’s a natural conclusion to me that many potential customers may have been window shopping far more during lockdown as their devices became their portal to any form of shopping outside of supermarkets. As Denise Lee Yohn writes in Harvard Business review writes, the pandemic has redefined our expectations of retail experiences, and customer behaviour is likely to change in many ways. This is likely to be amplified by a consumer market looking for maximum value as a global recession takes hold.

As our world shifted, I noticed that the retail categories I would traditionally consider great candidates for window shopping, were also the ones introducing queuing systems. Whilst supermarkets were under great strain and less likely to be multi session experiences (grocery shopping is a chore, even online, I won’t hear otherwise), the sudden surge in demand for DIY products meant stores such as B&Q and Wickes required you to queue for 45 minutes (in my experience, but in some cases far longer) just to view products on a website.

This resulted in queuing multiple times to simply view products, with each experience becoming more tiresome each time I heard the Queue-It ‘ding’ as I finally was granted access to perform my window shopping.

The reasons for this system were clear, and a small annoyance to a consumer is of little consideration in comparison to the health and safety of employees. However, the customer experience was completely altered by this queuing system. No longer could I viably compare prices, specifications or colours if I had to wait 30 minutes to start that experience each time.

What’s more, internal teams are losing access to valuable sessions to help accumulate data, which can be used to personalise experiences and help drive conversions. This sounds like a minor point but the impact on conversions personalised experiences have is clear. Monetate’s 2018 report found that customer experience which involved personalised content could convert from anywhere between double to ten times more than those without. A reduction in onsite browsing is likely to have impacted these internal research teams and, at the very least, is a missed opportunity as traffic would have been at an all-time high.

For anyone interested in customer experience, accepting that customers are window shoppers should raise alarm bells when we begin introducing queuing systems to prevent this action from happening. If this is a key customer journey, we are very unlikely to want to put up any kind of barriers to prevent this from happening.

So, why was putting a lock on the proverbial front door the go-to solution?

I think it’s fair to say that, until the pandemic hit, there won’t have been many digital product owners who would have been getting pressure to include and integrate features into websites that could help have a positive impact on public health. It’s something that very few could have predicted would impact digital businesses in the way it has. But I think the uniform way in which companies have implemented these safeguards shows that there is a fundamental disconnect between customer experience strategists and their technical counterparts.

Although some guesswork is involved, I’d suggest that none of the sites which have integrated these systems have done so due to the lack of scalable infrastructure. It’s highly likely that the teams behind these products have implemented all the requirements to allow their sites to scale up and down as traffic fluctuates. But it is, understandably, less likely that the infrastructure allows for the tweaking of features on a case by case basis.

This is interesting when we start to consider that (as was the case during March’s lockdown) we may need to limit the number of orders placed within a given timeframe. If we cannot control these features, for example the shopping basket or checkout functionality, at a micro level, it means we must limit the number of people accessing our product at any given time. Like at the supermarket, if we can't control what people put in their baskets or the queues at checkout, it makes sense to limit the numbers of people coming through the door.

To the product team, this makes sense, and is likely the quickest and easiest scenario to make sure orders can be limited. But customers are less understanding. They don’t care about the technical reasons why they cannot view the site, and instead silently get more frustrated as they wait for the digital queue to let them in to start their experience. The irony is that the popularity of these services means that they have greater exposure than ever before. If customers have negative customer experiences, what is the long-term impact of that on the business?

The truth is that technical strategists or product developers are often concerned about future proofing in a technical sense, but very often eschew the future proofing of the customer experience. Similarly, customer experience strategists may not understand the technical limitations of their product, and therefore must sacrifice customer experience due to business practicalities.

From a technical perspective this is easily solved. The tools and methodologies already exist to fix some of the problems that you may face in a similar scenario. We’ve helped clients implement feature gates; whilst the microservice architecture pattern has been heavily adopted across the development world to help isolate services and prevent systems becoming monolithic.

The more important aspect is developing a culture of customer centricity that forms the basis for your technical strategy. If your customer experience experts believe that this window shopper customer makes up a huge portion of the eCommerce customer base, then it’s also only a matter of time before a competitor creates a better alternative which caters to these customers whilst also being able to tightly restrict order numbers. In that scenario the gulf between your two strategists has created an opportunity for your customers to find a happier home. The sharing of knowledge between your technical and customer experience strategies is imperative to ensure that large portions of your customer base are not ignored because of some technical limitations.

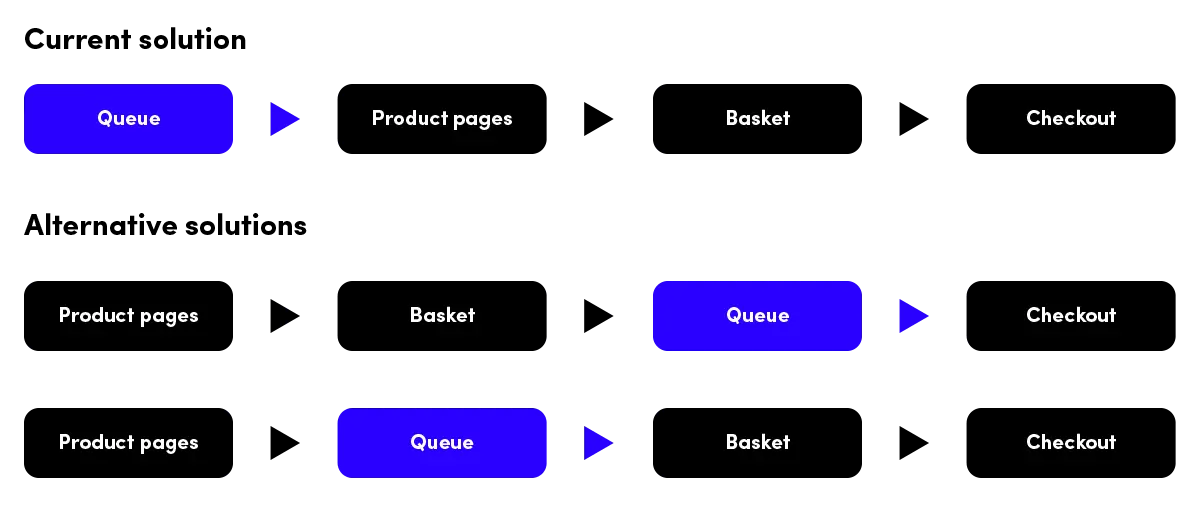

With the presumption that the queue-at-the-door style system adds a significant layer of friction to your window shopper customer personas, I think investigating alternatives is worthwhile.

I would suggest that by splitting out the checkout process using feature gating and microservice architectures, you could easily move the friction of queuing to a point in which customers have already committed to purchasing. Although this is not a perfect solution, it does offer some clear benefits.

Firstly, you allow your window shoppers to have a friction free experience until the point at which they’ve decided to purchase a product. This means they can come to your site over multiple sessions without any friction. On the presumption that a multi session shopper is a key customer journey for your business, this method allows for you to ensure that casual window shoppers have a positive experience.

Secondly, you can continue capturing data to aid content personalisation to help drive sales. By locking the door to your site, you’re giving up useful data which could be used to help inform similar decisions further down the road. Allowing window shoppers to feed into this data capture will continue to allow any marketing team to build up accurate pictures of customer behaviours without worrying about the impact of a queue system.

To me, the third potential benefit is particularly interesting. Most eCommerce platforms experience the traditional drop off in consumers from page view to purchase (Episerver's report has a cross industry average of around 4%). By moving the checkout process, you can assume the number of people queuing would be significantly less than those queuing to enter the site. Even a conservative drop-off from page view to checkout completion of 20% would result in 20% less people in the queue, therefore reducing wait times for those who have to go through any kind of queuing process. Consumer intentions to buy once they’ve reached the checkout also plays into your favour. Although a small study by littledata.io found that a checkout step completion average of 44.7%. Despite this still being relatively low, it is much higher than the 3% online average.

There are, as always, some caveats to this approach.

Due to the current consumer environment, the rulebook can be thrown out the window. It wouldn’t surprise me if implementing a queuing system would appear to significantly improve the number of customers buying items, as they feel they’ve made a time commitment and therefore might as well purchase something from you. Similarly, demand was so high during this period, that the number of people queuing may still reach a critical threshold and result in long wait times during a checkout process. It’s also impossible to have A/B tested given the reasons for implementing this feature in the first place.

I would argue, however, that putting your faith in any positive results from implementing a ‘front door’ queuing system is a dangerous game. Like other dark patterns, customer trust can be eroded when they feel that a product is designed to manipulate them into decisions. Forcing customers to wait because it seemingly increases customer conversion seems to me to be fool's gold. One competitor's move to change the expectations on queuing will nullify any positive metrics you may have and leaves the door wide open for your customers to find a better customer experience elsewhere.

Despite it being an extreme example, I feel like the move to queue-at-the-front-door systems can teach us a lot about the relationship between customer experience focused strategists and technical strategists. When we’re forced to make quick decisions, as many teams have had to during lockdown, it can shine a light on how we operate day to day. Fully embedding customer experience thinking into all your teams is essential to understanding how to deal with difficult decisions. Too often, customer experience is sacrificed due to technical limitations which may have been avoided through embedded customer experience thinking. At the very least, when we come to making these decisions, we want to have as many plays available to us as possible. Looking at how the queuing systems rolled out, it would suggest that there weren’t many teams in a position to create a more optimal customer experience than they ended up delivering. However, now we have the time and space to start thinking about how we can improve our customers' experience even when having to restrict features and functionality.

If this has resonated with you then get in touch – we’d love to help you give your consumers the optimal customer experience.